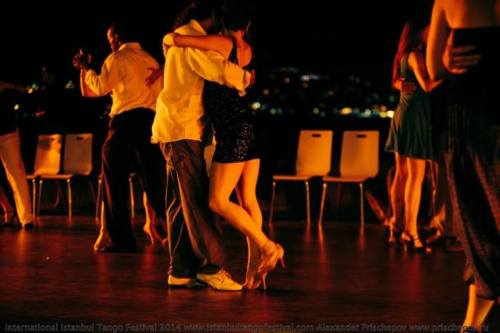

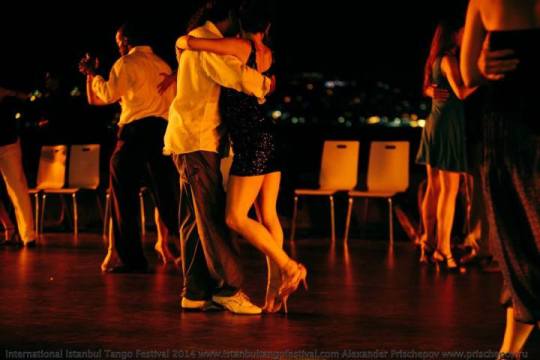

A few years ago, tango began a retrenchment. I first noticed it oozing from New York dancers visiting Boston in 2009, but soon saw it in Buenos Aires, felt its venom in Wellington and Sydney, and am now confronted with it regularly even here in radical Berlin.

The retrenchment takes the form of extremely simple dancing in which the focus of the dance is not on interesting improvisation, but on musicality, and specifically rhythmic musicality accompanied by quite bigoted claims about any other values and priorities which could be pursued while dancing tango. It also involves an extremely narrow subset of tango music, eschewing contemporary orquestras, post-1950s compositions, and world music. In Berlin one gets the sense that the line of dance is more important than what you are doing in it. This is called “social tango”.

That is the form. But I believe the substance of the retrenchment is sexism.

Last week I interviewed Andreas. I love to dance with him because he’s one of the few people who operates in a tango context with something approaching expressive freedom. It was he who used the term ‘Victorian’.

I’ve been dancing about 8 years. Here in Berlin there used to be much more creativity in the dancing. Now there is a new tendency to limit the range of moving the body in spite of all the skills we learned from 100 years of contemporary dance or Modern dance, (M. Graham, M. Cunnigham, P.Bausch….) and Tango Nuevo to open the body, to liberate the move, to explore movement in any direction, to learn from other disciplines. And what’s strange is that it’s mostly the young people! The dance in the classical scene remembers me sometimes of a new kind of Neo-Victorians. The new ideal is not to open their legs too much, to make small, elegant, controlled movements. They don’t want their bodies to move too much, too big, too expressive; one of the consequences is for them not to dance to Piazzolla or all the Tango Nuevo Maestros or Neotango-Music. Dino Saluzzi? Give him a concert hall, but don’t dance to his music. Don’t be too wild. Be civilised, be elegant. How can someone who is young not allow their body to be free? How is this possible after the sexual revolution? And this is Berlin!

This movement goes by different names in different places. In NZ it is called “milonguero style”, in AU it is called “salon style”, and in Berlin it is called “social tango” or “marathon style” (after the inexpensive weekends where European dancers gather for 2.5 days of non-stop dancing).

I have been researching the origins of this boring, strange, and negative phenomenon.

Carolyn Merritt’s book, Tango Nuevo (which I have reviewed at length here), offers three insights into the retrenchment. The first is the influence of Susannah Miller’s lucrative invention of “milonguero style” in 1995 and her myth-making marketing claims around “authenticity“. The second is young Argentines’ effort to protect tango as patrimony in the late 2000s. (This was necessary for several reasons: Buenos Aires milongas were flooded with foreign tourists – many of whom were worryingly masterful; foreigners won too many top places in the Campeonato Mundial/World Championship; and aspiring professionals needed to simultaneously prepare for and resist the definitions of tango wielded by the foreign gatekeepers of the global Argentine Tango industry.) The protection took the form of deemphasizing meritocratic virtuosity in favor of nurturing young Argentines into a more accessible, social, and less demanding tango practice, while insulating some milongas from tourists. Merritt’s third contribution is explosive, although she refrains from vigorous pursuit of its significance. She reports that Gustavo Naveira’s mid-1990s Cochabamba Investigation Group (from which emerged the second-wave use of ‘Tango Nuevo’) significantly empowered women.

I am routinely accused of dancing Tango Nuevo. In short, the difficulty with this term is that Naveira’s 1990s version was only a comprehensive systematization of movements which had existed since the 1940s, when Petróleo used the phrase ‘tango nuevo’ to promote his innovations. Nevertheless, people all over the world claim to be able to identify “Nuevo” at a glance, as the contemporary depravity which disregards the authenticity of the Golden Age. I believe that what they are seeing is not about movement vocabulary but about the woman’s agility, flexibility, and range in the dance. Roughly a decade after Naveira broke sequences into movements, with the effect of accelerating marks’ personal improvisation, Dana Frìgoli and others developed methods for more fluid, powerful, and visible responses to the mark.

Another decade later we have the retrenchment. Frìgoli’s influential technique is not being used in milongas, despite being ubiquitous in professional performances. The milonguera’s dance became more fluid and independent for ten years and now is back to something with the appearance of untrained rag-doll. Andreas is generous with the term “elegant”. I can count on one hand the girls with elegant feet I’ve seen in Berlin – and several were visitors.

To read the full article by Vio, TangoForge click the link below: